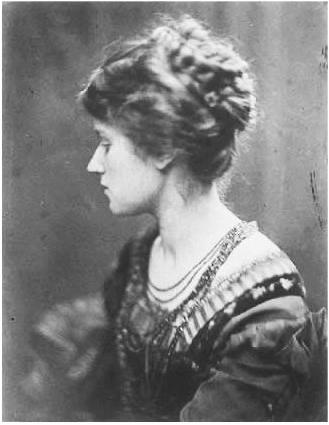

Marie Euphrosyne Spartali, later Stillman, born 10 March 1844, was a British member of the second generation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Of the Pre-Raphaelites, she had one of the longest-running careers, spanning sixty years and producing over one hundred and fifty works. Though her work with the Brotherhood began as a favourite model, she soon trained and became a respected painter.

Known for their Greek heritage and beauty, Marie along with her cousins, Maria Zambaco (an artist and model) and Aglaia Coronio (embroiderer, bookbinder, art collector and patron of the arts), were known collectively among friends as "the Three Graces," after the Charites of Greek mythology (Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia). Beauty aside, Marie cut an imposing figure, standing at 1.9 meters (6ft 3) and, in her later years, dressed entirely in black, purposefully attracting much attention throughout her life.

In the house of the Greek businessman A.C. Ionides at Tulse Hill, in south London, Marie first met artist James Abbot McNeil Whistler and playwright Algernon Charles Swinburne. The meeting made quite the impression, for Swinburne was reported to have said that "She is so beautiful that I want to sit down and cry".

In 1864, Whistler introduced Marie to the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She began sitting for him and when Marie expressed interest in learning to paint he referred her to Ford Madox Brown. Over the next five years the pair developed a close, almost familial, relationship. Of his models, Brown said that Marie was “the most intellectual,” and maintained a deep respect for her work, chronicled in their correspondence.

Because of her close links to the Brotherhood Marie is often identified as part of the second generation of the movement. According to Henry James, “She inherited the traditions and the temper of the original PRs...but she has come into her heritage by virtue or natural relationship. She is a spontaneous, sincere, naive Pre-Raphaelite.”

There is, however, some academic debate as to whether this is entirely accurate. For example, Robert de la Sizeranne of Le Correspondant noted that this new generation of Pre-Raphaelites, Marie among them, had enough in common with the Symbolists to be considered one. She could be considered a candidate for Symbolism because her figures "... have an immobility, a silence, a pose almost suspended, a slow hesitation in their rare movements, which make them resemble something like sleepwalkers.” Rossetti himself credited Marie for her ability to infuse her figures with emotion, thereby elevating them to something more than mere images.

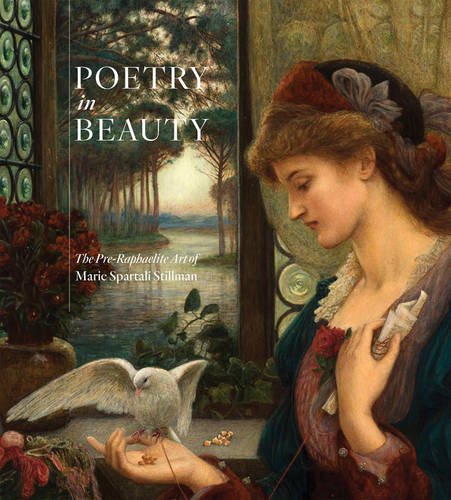

Love's Messenger

Painted with watercolour in 1885, it depicts

a dove that has carried a love letter to a woman standing in front of an open window. She wears a red rose, and has just put down her embroidery of a blind-folded Cupid. She holds the letter to her chest as the dove eats from the palm of her hand, a piece of string still connecting the dove to the letter. The blind-folded Cupid points a loaded arrow towards her. The artist modestly described the painting in 1906:

"I wish I could tell you something interesting about my pictures at Mr. Bancroft's, they are merely studies of heads done for the pleasure of painting. The effect of a fair head in a certain bull's eye window of a friend's studio where I was working one winter suggested Love's messenger - that is all... [Love's Messenger] is merely a study from a model. My daughter Effie who was then at school [was] not able to sit for me to complete it from her. I painted a landscape from the Villa Borghese Rome as the background when I made several changes in the picture while in Rome."

Love's Messenger reflects the influence of both early Pre-Raphaelite painting and Italian Renaissance painting. The symbols portrayed in the painting, including the dove, rose, ivy, and the blind-folded Cupid "suggest constancy, fidelity, and loveliness in full bloom," but also suggest "beauty on the cusp of decay, sensuality, and the pain Cupid's arrows may inflict." The presence of Venus has been interpreted from the rose and the dove, so that the "scene may offer a contrast between the beauty, love, and abundance of Venus and the sensuality and unpredictability of her son Cupid."

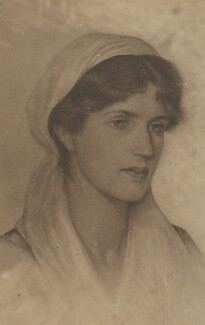

Beatrice

Alongside her husband, Spartali-Stillman lived in Florence, Italy for a number of years. She took great inspiration from the city around her which can be seen most prominently in her subject matter. Being in the city of Dante Alighieri, she depicted numerous scenes from the Divine Comedy, focusing in particular on the romance between Dante and Beatrice.

The painting depicts Dantes beloved Beatrice who appears in both the Vita Nuova and Purgatory. While Dante’s Beatrice is described in terms of the divine, Marie paints a more earthly beauty, lost in thought as she contemplates her reading. A bow of deep red roses climb the wall behind her, fallen petals resting near her book, by her arm sits a handful of pansies. A small sprig of yellow jasmine is tucked behind her ear. In the Victorian language of flowers, a burgundy rose means 'unconscious beauty', pansies mean 'thoughts' and yellow jasmine means 'grace and elegance'.

It was an Italian woman named Beatrice di Folco Portinari who has been commonly identified as the principal inspiration for Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, and is also commonly identified with the Beatrice who appears as one of his guides in the last book of the Divine Comedy, Paradiso, and in the last four canti of Purgatorio. There she takes over as guide from the Latin poet Virgil because, as a pagan, Virgil cannot enter Paradise and because, being the incarnation of beatific love, as her name implies, it is Beatrice who leads into the beatific vision. Just as Virgil represents human reason, so does Beatrice represent divine revelation, theology, faith, contemplation and grace.

Scholars have long debated whether the historical Beatrice is intended to be identified with either or both of the Beatrices in Dante's writings. She was apparently the daughter of the banker Folco Portinari, and was married to another banker, Simone dei Bardi. Dante claims to have met a "Beatrice" only twice, on occasions separated by nine years, but was so affected by the meetings that he carried his love for her throughout his life.

Dante's Divine Comedy was a theme for many of the Pre-Raphaelites, including Maries teacher Rossetti. Marie painted Beatrice a second time, depicting her holding a bowl of red roses in her right hand continuing the theme of 'unconscious beauty'. She holds a stem of white lilies in her left which represents 'purity and sweetness', and on her head she wears a crown of blue cornflowers which symbolises 'delicacy, refinement and devotion'.

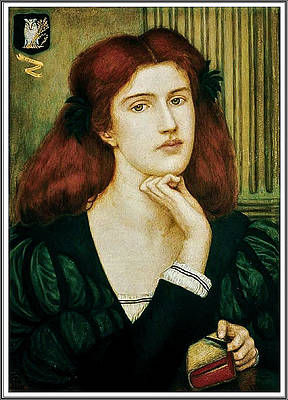

Madonna Pietra degli Scrovigni

Madonna Pietra degli Scrovigni depicts the cold, heartless woman of Dante's poem of the same title:

Utterly frozen is this youthful lady, Even as the snow that lies within the shade;

For she is no more moved than is the stone...

A while ago, I saw her dressed in green,– So fair, she might have wakened in a stone

The painting depicts a woman standing in an olive green robe trimmed with gold, a flower is pinned to the front of her dress alongside a red heart shaped pin encrusted with diamonds. She wears a crown of green hellebores, in her right hand she holds a small crystal ball and in her left she holds a branch of blossom above her head, creating an curved arch of white flowers over herself. She stands in front of an oak tree with a placid expression on her face, a stream forks into the distance behind her.

Hellebores can have very contrasting meanings from 'tranquility' to 'scandal'. White blossom was seen as a tribute to beauty. Oak trees have even more meanings that hellebores including hospitality, healing, health, strength, endurance, majesty, wisdom, protection, luck and wisdom.

Inside the small crystal globe that the Madonna holds, one can just make out the image of the Annunciation. This has been suggested as a reference to the Feast of the Virgin on 25 March, marking the end of the winter, a motif widely employed in Florentine religious art. The globe itself plays a useful role in simultaneously enclosing and making a feature of the reference.

A Rose from Armida's Garden

Painted in 1894 A Rose from Armida's Garden is inspired by the poem Jerusalem Delivered by 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. Tasso composed this first epic poem at the age of eighteen. It tells a largely mythified version of the First Crusade in 1099.

Armida, a Saracen sorceress, has been sent to stop the Christians from completing their mission and is about to murder the sleeping soldier, Rinaldo, the greatest of the Christian knights, but instead she falls in love and abducts him in her chariot.

She creates an enchanted garden of roses where she holds him a lovesick prisoner. Eventually Charles and Ubaldo, two of his fellow Crusaders, find him and hold a shield to his face, so he can see his image and remember who he is. Rinaldo can barely resist Armida's pleadings, but his comrades insist that he return to his mission. Armida is grief-stricken and raises an army to kill Rinaldo and fight the Christians, but her champions are all defeated. She attempts to commit suicide, but Rinaldo finds her in time and prevents her. Rinaldo then begs her to convert to Christianity, and Armida, her heart softened, consents.

In her painting Marie depicts Armida standing in her rose garden at sunset, holding a pale pink rose to her chest. With the other hand she leans the stem of two roses towards her which results in their petals falling away, most likely a symbol of the heartbreak of Rinaldo's abandonment. In the language of flowers a pale pink rose means passion and desire, a withered rose mean 'I would rather die'.

The Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansaldo

Also titled Messer Ansaldo showing Madonna Dionara his Enchanted Garden, the painting illustrates a tale from The Decameron, a collection of novellas by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio. The book is structured as a frame story containing 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men; that were sheltering in a secluded villa just outside Florence in order to escape the Black Death, which was afflicting the city. To pass the evenings, each member of the party tells a story each night, except for one day per week for chores, and the holy days during which they do no work at all, resulting in ten nights of storytelling over the course of two weeks. Thus, by the end of the fortnight they have told 100 stories.

In the fifth tale narrated by Emilia, a nobleman Messer Ansaldo is in love with Madonna Dianora, a married woman, and often sends her messages of his love. She does not return his affections, and in an attempt to put him off says that she will only be his if he can prove his love by providing for her a garden as fair in January as it is in May. Messer Ansaldo hires for a great sum a necromancer, and thereby gives her the garden. Madonna Dianora tells her husband of her promise, and he says that, while he would prefer that she remain faithful to him if possible, she must keep her word to Messer Ansaldo. When Messer Ansaldo learns of this he releases her from her promise and she returns to her husband. From then on Messer Ansaldo felt only honorable affection for Madonna Dianora. The necromancer is impressed by this and refuses to take any payment from Messer Ansaldo.

In the painting Marie depicts the a walled garden in the peak of spring. Through arched doors the true weather of the season can be seen, a flurry of snow falls creating a thick blanket, a castle can be seen in the distance of this icy scene. In sharp contrast to the world beyond its walls, the garden is brimming with spring flowers.

In a raised bed at the centre of the courtyard, daffodils, irises and tulips are among the many in the display, a cherry blossom is the centre piece of the display, one of Madonna's companions looks up at it in complete disbelief. In the left corner of the garden another of Madonna's companions is picking roses, three already in her hand, held close to her chest, after having a long winter deprived of flowers, is engrossed in the roses beauty.

Madonna stands at the centre of the scene, her head bowed at the unfortunate results of her promise, with three boys surrounding her holding up to her golden plates of flowers and fruits from the garden, wearing open shoes on lush carpet of grass and delicate flowers. Messer Ansaldo smiles at his achievement of what should have been an impossible task, donning a bright white robe of complicated embroidery and a flower crown, a striking contrast to the heavy fur coats of his guests.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

The Pre-Raphaelite Art of by

Marie Spartali Stillman Jan Marsh

Comentários