John William Waterhouse RA, born 6 April 1849, was an English painter known for working first in the Academic style and for then embracing the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's style and subject matter. His artworks were known for their depictions of women from both ancient Greek mythology and Arthurian legend.

Hylas and the Nymphs

Hylas and the Nymphs, painted in 1896, depicts a moment from the Greek and Roman legend of the tragic youth Hylas, based on accounts by Ovid and other ancient writers, in which the enraptured Hylas is abducted by Naiads (female water nymphs) while seeking drinking water.

Hylas was the son of King Theiodamas of the Dryopians. After Hercules killed Hylas's father, Hylas became a companion of Hercules and later his lover. They both became Argonauts (a band of heroes) accompanying Jason in his quest on his ship Argo in seeking the Golden Fleece. During the journey, Hylas was sent to find fresh water. He found a pond occupied by Naiads, and they lured Hylas into the water and he disappeared. According to the Latin Argonautica of Valerius Flaccus, they never found Hylas because the latter had fallen in love with the nymphs and remained "to share their power and their love." The poet Theocritus, on the other hand, has the nymphs shutting his mouth underwater to stifle his screams for Hercules.

In the painting Waterhouse depicts Hylas, a male youth in classical garb, wearing a blue tunic with a red sash, and bearing a wide-necked water jar. He is bending down beside a pond in a glade of lush green foliage, reaching out towards seven young women, the water nymphs, who are emerging from the pond among the leaves and flowers of Nymphaeaceae (water lilies), including an early depiction of the yellow waterlily, Nuphar lutea. The nymphs are naked, their alabaster skin luminous in the dark but clear water, with yellow and white flowers in their auburn hair. They have very similar physical features, perhaps based on just two models.

Hylas is being enticed to enter the water, from which he will not return. One of the nymphs holds his wrist and elbow, a second plucks at his tunic, and a third holds out some pearls in the palm of her hand. The face of Hylas in profile is shadowed and barely visible, but the faces of the nymphs are clearly visible as they gaze upon him. The scene is depicted from a slightly elevated position, looking down at the water like Hylas, so no sky is visible. Hylas's position forces the viewer's focus onto the nymphs in the water and the lack of reference to his relationship with Hercules emphasizes that the narrative of the painting is not about Hylas's experiences, but about the sinister nature of the nymphs.

Lamia

Lamia in ancient Greek mythology, was a child-eating monster and, in later tradition, was regarded as a type of night-haunting daemon. In the earliest stories, Lamia was a beautiful queen of Libya who had an affair with Zeus. Upon learning this, Zeus's wife Hera forced Lamia to eat her own children, the offspring of her affair with Zeus, and afflicted her with permanent insomnia.

The Lamia also became a type of phantom synonymous with the empusai (a shape-shifting female being in Greek mythology) ascribed with serpentine qualities, who seduced young men.

An account of Apollonius of Tyana's defeat of a Lamia seductress inspired the poem Lamia by Keats in 1820. It was Keats’s poem that inspired Waterhouse's Lamia in 1905. Set in the wild hills of ancient Greece during an ‘evening dim at moth time’, the poem speaks of a young charioteer who hearing a soft voice calling - ‘a maid more beautiful than [any] ever twisted braid’ - falls inextricably in love with her. He is unaware that this vision is in reality a monstrous half-serpent, who metamorphoses into a woman’s form to prey on young men.

The intensity of the young knight’s gaze draws the viewer into Waterhouse’s painting, Lamia kneels below him, one hand on his and the other resting on his arm plate, the only visual clue to her nature captured in the glimmering moulted snake-skin draped about her, its peacock tinges drawn from Keats’s description. Waterhouse also painted a second version of Lamia in 1908 sat by the water wrapped in the same snakeskin as she combs more of it from her hair with her fingers.

Ophelia

Waterhouse painted Ophelia in 1894. It depicts a character in William Shakespeare's drama Hamlet. She is a young noblewoman of Denmark, a potential wife for Prince Hamlet.

Ophelia is depicted, in the last moments before her death, sitting on a willow branch extending out over a pond of lilies. Her royal dress strongly contrasts with her natural surroundings. Her elaborate dress features jewels and embroidery in gold flourishes on the trims with a Lion motif at the base.

Ophelia has a bunch of daisies lying in her lap and a poppy and daisy wreath in her hair. In the Victorian language of flowers daisies symbolise innocence and purity. Victorians had a variety of meanings for poppies based on the colour, including consolation for loss, deep sleep, and extravagance. Red is linked to death, remembrance, and consolation. There is also a small wild rose at her feet which in Greek mythology is a powerful symbol of love and adoration. Waterhouse painted Ophelia several times, with the lion appearing on her dress again and each portrait containing daisies, continuing the theme of innocence and youth.

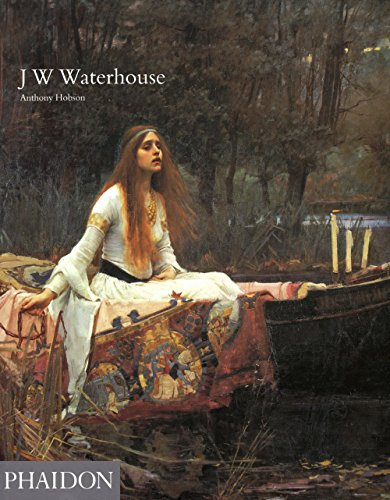

The Lady of Shalott

The Lady of Shalott, painted in 1888, is a representation of the ending of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's 1832 poem of the same name. It depicts a scene in which the poet describes the plight and the predicament of a young woman, loosely based on the figure of Elaine of Astolat from medieval Arthurian legend, who yearned with an unrequited love for the knight Sir Lancelot, isolated under an undisclosed curse in a tower near King Arthur's Camelot. Waterhouse painted three versions of this character, in 1888, 1894 and 1915. It is one of his most famous works, which adopted much of the style of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the painting has the precisely painted detail and bright colours associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, though Waterhouse was painting several decades after the Brotherhood split up during his early childhood.

In the poem, the Lady had been confined to her quarters, under a curse that forbade her to go outside or even look directly out of a window; her only view of the world was through a mirror. She sat below the mirror and wove a tapestry of scenes she could see by the reflection.

After defying the curse by looking out the window at Sir Lancelot riding in to Camelot, the Lady has made her way to a small boat. This is the moment that is pictured in Waterhouse's painting, as the Lady is leaving to face her destiny. She is pictured sitting on the tapestry she has woven.

The Lady has a lantern at the front of her boat and a crucifix is positioned near the bow. Next to the crucifix are three candles. Candles were a representation of life – two of the candles are already blown out, signifying that her death is soon to come.

Aside from the metaphoric details, this painting is valued for Waterhouse's realistic painting abilities. The Lady's dress is stark white against the much darker hues of the background. Waterhouse's close attention to detail and colour, the accentuation of the beauty of nature, realist quality, and his interpretation of her vulnerable, wistful face are further demonstration of his artistic skill. Naturalistic details include a pied flycatcher and the water plants that would be found in a river in England at this time.

"And down the river's dim expanse

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance

With glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott."

Psyche Opening the Door into Cupid's Garden

Waterhouse painted Psyche Opening the Door into Cupids Garden during the height of his career, in 1904. One year earlier, the artist also concluded an oil painting depicting the mythological character, with the same physical attributes and garments, in the work Psyche Opening a Golden Box.

Waterhouse depicts the nymph timidly pushing open a large, wooden door. She has light skin, and red-brown hair pulled back in a bun. Her soft pink dress is flowing and creates beautiful folds and crests as she holds part of the skirt with one hand, along with a small, red rose. One of her sleeves falls her arm, exposing her bare shoulder. Psyche peaks into the garden of her true love with a concerned expression.

As a reference to the ancient Greek architecture, the door features an arc, and the walls have golden details with faces of angels – or Cupid himself. There is a tree behind the model, and many rose bushes near the door with white and pink blossoms. Cupid’s garden can be partially seen by the gap of the open door. A ceramic vase is by the entrance, and a field of grass leads up to a summerhouse made of Greek columns.

Boreas

Painted 1903, the painting is titled Boreas, after the Greek god of the north wind and it shows a young girl buffeted by the wind. The 1904 Royal Academy notes described the subject of the painting as:

In wind-blown draperies of slate-colour and blue, a girl passes through a spring landscape accented by pink blossom and daffodils.

In the Victorian language of flowers daffodils mean regard, what one tucked behind her ear might mean I couldn't say. It is possible that Waterhouse simply picked a winter flower but things are never so simple when it comes to symbolism in paintings.

Waterhouse had painted another portrait in this pose, Windflowers in 1902. The subject is seen struggling with the wind which flusters her hair and clothing, whilst she clings onto her recently collected flowers. There have been suggestions that the myth of Proserpina is loosely touched on in this painting because the spring flowers in this scene would have been similar to the ones in the vale of Enna when Proserpina was famously swept away. The flowers she has collected are poppies in various colours which could mean consolation, sleep or time.

The Soul of the Rose

The Soul of the Rose, sometimes known as My Sweet Rose, was completed by Waterhouse in 1908 and took inspiration yet again from the literature of Tennyson.

The Soul of the Rose is a phrase that derives from Tennyson's poem titled Maud from 1855. The poem included the line 'And the soul of the rose went into my blood'.

In Waterhouse's painting a woman with auburn hair intertwined with white gems gently leans against a garden wall, pulling a soft pink rose towards her to smell its delicate fragrance. Her robes are peacock blue with gold embroidery and lined with a pink that matches the heart of the roses. The painting captures that wonderful moment of being enveloped by the heady scent of a rose, forgetting everything else around her in those few short moments of heavenly scent, her eyes soft and almost closed for the intimate act.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

by by

Anthony Hobson Jessica Findley

Comentarios