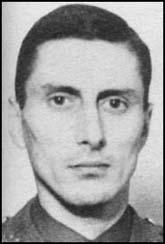

Brian Julian Warry Stonehouse MBE, born 29 August 1918, was an English painter and Special Operations Executive agent during World War II.

He was born in Torquay, England and had a brother, Dale. When his family moved to France, he went to school in Wimereux, Pas-de-Calais. Back in Britain in 1932, he studied at the Ipswich School of Art.

Stonehouse worked as an artist but joined the Territorial Army after the outbreak of World War II. He was later conscripted into the Royal Artillery. In 1940, he worked as an interpreter for French troops in Glasgow who had been evacuated from Norway. In the autumn of 1941, he was training for a commission in the 121 Officer Cadet Unit when the Special Operations Executive contacted him. Due to his fluency in French, SOE recruited him as a wireless operator with code name of Celestin.

On 1 July 1942, Stonehouse parachuted into occupied France near the city of Tours in the Loire Valley. His radio got caught in a tree and he spent five nights in the forest before he could get it down. After finally retrieving it, the radio would not work properly and his contact told him to move to Lyon. In September, accompanied by another agent, Blanche Charlet, he went to a safe house and made contact with the other SOE agents. By August he was in regular contact with the SOE station in London. However he became careless and transmitted too much and too long. As a result, German direction-finders triangulated his position and the Milice arrested him on 24 October 1942 in Chateau Hurlevent near Lyon.

In Castres prison, the Gestapo placed Stonehouse in solitary confinement while subjecting him to frequent and brutal interrogations. In December he was transferred to Fresnes prison in Paris and further interrogated. Eventually he was shipped to Germany with other SOE prisoners, including Albert Guerisse, GC, the Pat O'Leary Line organiser, and Guerisse's Australian W/T operator, Tom Groome. In October 1943, they arrived in Saarbrücken and in November was sent to Mauthausen concentration camp. He spent a brief time in a Luftwaffe factory camp in Vienna. In mid-1944, he was transferred to the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp in Alsace with Guerisse, a.k.a. Pat O'Leary. Stonehouse saved his own life by drawing sketches for the camp commandant, guards and their families. Throughout his time in five prisons, Stonehouse kept his personal vow of never painting or drawing an officer in uniform.

From Natzweiler-Struthof, Stonehouse was sent to the Dachau concentration camp from where he was liberated by U.S.troops on 29 April 1945, along with below agent Bob Shepherd. A week later both agents were back in England. At home, he was created a military MBE. After the war, he remained in the military and was promoted to captain while working for the Allied Control Commission in Frankfurt, Germany where he assisted with the interrogation of Gestapo and SS members.

He was able to use his exceptional visual memory to serve his country once more. Officials from SOE were trying to find out what had happened to four of their female officers; Stonehouse was able to draw from memory four well-dressed women that he had seen being taken to their deaths by the Nazis the year before. The four female SOE agents, Andrée Borrel, Vera Leigh, Diana Rowden and Sonya Olschanezky. His sketches matched their photographs. As a result, their files were closed and their families were informed of their deaths.

In an ironic twist of fate, Stonehouse found himself interrogating Arnold Schneider, the very Nazi who had sentenced him to be shot as a spy. Stonehouse was handed a pistol and given permission to execute Schneider, but he refused, saying that he bore no malice to the Germans and had drawn down the curtain on this part of his life.

Stonehouse moved to New York with his friend Major Haller in 1946 and continued his career as a fashion artist. Crossing the Atlantic, Stonehouse aimed to become a portraitist and Haller’s social connections gave him an immediate entrée into New York society. He was attracted to the style of wealthy women who came to sit for their portraits. In addition to capturing their faces he drew their elegant clothes and jewellery.

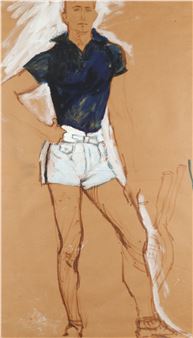

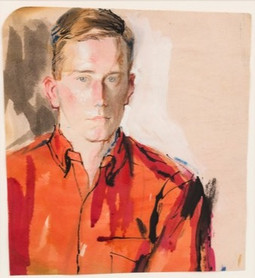

He had a particularly keen eye for gloves and hats and his flair caught the attention of Jessica Daves at American Vogue, who hired him as staff illustrator. "At Vogue, Stonehouse drew some of the world’s most beautiful women and his drawings startle with their poise, vitality and stylish originality. His style helped shape this elegant era: his designs look spontaneously effortless – rather like ballet. The fluidity and beauty of his work – characterised by its dramatic, sweeping black lines and striking use of colour – encapsulate post-war optimism and opulence." He received other commissions from the fashion industry, Harper's Bazaar and Elizabeth Arden.

"A golden decade followed as Stonehouse became a sought-after star of the New York fashion scene and women flocked to him. New York hostesses loved his impeccable manners and chiselled features. His mantelpiece heaved with invitations to their black-tie dinners and he was befriended by stars such as Tallulah Bankhead."

"He treated his models with kindness and they loved working with the tall, handsome and debonair Englishman. A few of them, such as Pauline Thomas, became part of his world for decades. At Vogue, Stonehouse’s exquisite fashion illustrations competed with artists such as René Gruau, Carl Erickson and René Bouché. During these years he was a financial success and his drawings began to appear regularly in ads for Saks Fifth Avenue."

Stonehouse’s association with Vogue ended with the issue published on 1 October 1962, but he continued working for Elizabeth Arden until the 1980s. Celebrity photographers may have dominated the 1960s, but in recent years fashion illustration has enjoyed a new popularity with the emergence of a generation of artists, including the celebrated David Downton, drawing inspiration from 20th century designers. The best 1950s pictures are now sought after as collectable artworks in their own right.

During the 1970s, he began to experiment with his drawings and excelled at drawing male models, it later emerged that he was gay when he had an affair with a male Swedish film star.

In 1979, he returned to Britain and became a portrait painter. His clients included members of the Royal family. One of his last portraits of The Queen Mother, who sat for him many times, still hangs in the Special Forces Club in London. During his final years Stonehouse was an active Theosophist living at the London branch of the United Lodge of Theosophists.

Brian Stonehouse died of a heart attack in 1998, aged 80, in London. Whilst operating in France Stonehouse continued to sketch and draw people he came across. He was on several occasions told not to carry his sketch books with him whilst 'on duty'. Throughout his times in various prisons he continued to draw, at first secretly, but after discovery more openly. His collections of drawings of fellow SOE prisoners, life in prison and prison guards along with other personal artefacts was handed over by the Stonehouse Family to the Imperial War Museum London in May 2007. These included, as well as the War Art, for example, postwar letters from surviving SOE operatives and letters and photographs from US President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

This last collection included a signed photograph and note from Eisenhower upon meeting Stonehouse again shortly after the war ended. This stated that upon meeting each other again, Stonehouse asked Eisenhower if he knew why he had survived the war. The response from Eisenhower was, "I was going to ask you that". Moyse's Hall Museum Bury St Edmunds discovered and facilitated the handing over of the collections following a VE Day exhibition, to which the family had brought Brian's art and other personal artefacts.

A series of exhibitions of Stonehouse's fashion work was held at the Abbott and Holder gallery in London from 2014 to 2017. Philip Athill, managing director of the Abbot and Holder art dealer in London, has collected Stonehouse's work.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

In 1997 he told his remarkable story, on Timewatch. A clip of the episode 'Secret Memories' can be watched via the image below on the BBC Archive Twitter.